Jersey City - Why a ‘Tree Census’ Makes Cents

Sustainable Jersey City uses crowdsourcing to press business case for urban forestry

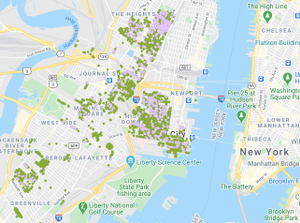

Over the past year, 300 residents of Jersey City have fanned out across 35 of its neighborhoods to take stock of the trees. Using a mobile app and some basic tools (including their arms), these trained volunteers have been recording vitals statistics—like species, diameter and circumference—and plugging them into a live map of the city’s urban tree canopy.

What looks like tree hugging is actually data collection, says Debra Italiano, founder of Sustainable Jersey City, the educational 501(c)3 nonprofit behind this crowdsourced census. When the two-year project wraps up, Italiano hopes it will be the first step to achieving stronger legal protections of Jersey City’s mature trees, and a robust, continuous municipal investment in urban forestry.

Environmentalists are often dismissed as tree huggers with spiritual or philosophical motives that obstruct economic progress. But actually the opposite is true, Italiano says. While environmentalists, like most people, appreciate trees from an aesthetic standpoint, their goals in wishing to preserve them are largely pragmatic. There’s a business case to be made for protecting Jersey City’s tree canopy, she says, and citizen scientists are helping her make it.

The Shrinking Canopy

So far citizen scientists have mapped nearly 5,500 trees, Italiano says, and the preliminary results confirm a trend that’s been happening for years: the loss of big trees in Jersey City’s urban neighborhoods.

The problem has been recognized since at least 2015, when a city-commissioned study measured the tree canopy at an unhealthy 17 percent. In response, a goal was set to plant 30,000 trees, in order to bring the canopy cover up to 20 percent. That never happened, Italiano says. Instead, just a few hundred trees a year have been planted, and the canopy has continued to shrink through die-off or development. Initial data from SJC’s new census reflects 6 percent deterioration between 2015 and 2020.

So what’s the point of a census that proves something you already know?

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” Italiano says. “We want to create the business case for urban forestry investment and educate municipal officials, because sustainability issues can sometimes be a little abstract.”

The innovative database SJC is using doesn’t just count trees. It calculates each tree’s economic value to the city based on an algorithm developed by the U.S. Forest Service. Mature trees filter pollutants from the air, offsetting emissions from buildings and traffic. They absorb heat from concrete and asphalt, lowering utility bills. They soak up stormwater, helping prevent flooded streets and sewers.

Scientists have long understood those benefits. So have city planners. But when those benefits are calculated in real time, down to the individual tree, they can be a powerful tool for shaping municipal policy, Italiano says.

“So here’s the business case,” she says. “If I look at the map now, I’m looking at 5,450 trees, and the annual monetized benefits, or cost savings, to the city is about $360,000 a year. That’s compelling, for just 5,450 trees. And we’re projecting that there are approximately 100,000 trees in Jersey City.”

She says putting a price tag on the consequences makes it easier to persuade the city not to chop down a mature oak just because it’s buckling the sidewalk, and not to let developers plant saplings in place of 20-inch-girth trees that deliver 10 times the eco-benefits. She also hopes to reverse the trend of reserving shade trees for parks and planting ornamental trees on urban streets, where a broad tree canopy is most needed.

In Jersey City, development has been a major driver in the loss of big trees, and the financial consequences have been considerable even if they weren’t officially measured. Italiano notes that after 84 mature sycamores were cut down for development in Society Hill, nearby homeowners saw their utility bills skyrocket. At the time there was no attempt to calculate the cost in terms of dirtier air or stormwater runoff, but “we’re purporting that (the loss of) this climate mitigation opportunity . . . is no small consideration,” Italiano says.

Pushing on All Fronts

The census is the first part of Italiano’s three-part strategy to shape the future of sustainability in Jersey City. She plans to use it as leverage to convince the city to close loopholes in its current tree ordinance per U.S. Forest Service best practices, and to create mandatory funding for tree planting.

She thinks she can get help through the census itself—not just because its eco-benefits calculator can deliver a compelling business argument, but because the software allows various stakeholders to access tree data in a way that’s relevant to them.

Click on the Tree Map, Italiano says, and the data is viewable by ward (“important to councilpeople”); neighborhood (“important to neighborhood associations”); park (“important to the Parks Coalition”); and Special Improvement District (“important to those business managers”). She plans to integrate the U.S. Forest Service’s stewardship map (STEW-MAP), which will help citizen organizations coordinate their efforts to protect Jersey City’s tree. She also hopes to map the 30 to 40 percent of tree canopy that grows on private land. A couple of local universities are already on board.

“We’re pushing on all fronts,” Italiano says.

They’re also pushing the idea out to other municipalities, by offering to customize, host and support the tree census database for them for $1,000.

“We look at that as a valuable service tier that SJC can offer other municipalities for green infrastructure in managing their urban tree/forestry assets,” she says.

It’s also a valuable way to keep SJC sustainable. Just more proof that tree huggers are business savvy too.

For more information, visit Sustainable Jersey City. To see SJC’s open-source map, click here.

Going Solar without the Panels

See more details on SJC's community solar project at: sustainablejc.squarespace.com/projects/community-solar